Choose the Right Door:

Understanding the Monty Hall Problem

The Monty Hall problem is an absolutely fascinating riddle which stumps most at first. This is because what appears to be the correct answer is usually thought upon instantly with little to no logical reasoning. To summarize the Monty Hall problem, a contestant chooses one random door out of three, only one of which contains a prize. the other two contain goats. Once a random door is picked, an unchosen door, not including the one with the prize behind it, is removed from play. Then, the contestant is offered to trade their door with the remaining unselected door. The question is whether a person has a better chance of selecting the door with the prize by staying with their pick or switching to the remaining one. Through deductive reasoning, it is easy to figure out that switching doors actually yields a better chance at electing the correct door.

First and foremost, to understand this problem, it must be understood that there are three different doors with three different choices. One door has a prize, one door has a goat, and another door has a goat. Sure, the two doors contain goats, but the second door provides a third possible spot for the prize to be held. The problem is not whether the contestant walks away with a prize or a goat, but weather they walk away with a prize, a goat, or a goat.

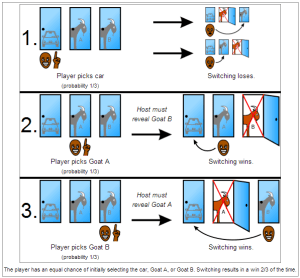

Take a look at this public domain image available from the Wikimedia Commons

This is the Monty Hall problem and every outcome in a nutshell. It shows every possible door when it is picked along with every probable outcome so long as the algorithm of always picking the other door is followed. It proves how a 2/3 outcome is achieved so long as doors are always switched.

There is another way to look at the problem if it still seems confusing. As explained in this article titled “Understanding the Monty Hall Problem,” There could be 100 doors in this problem rather than just three. 99 of these doors contain goats while just one contains a prize. Instead of only taking one door out of play, Monty removes 98 different doors, none of which being the door with the prize. with these rules, the normal 2/3 chance from the original problem suddenly becomes a 99/100 chance. If put in this situation, the reason to switch is much clearer than it was before. Through my own experimentation using a simulator, out of 100 tests, using 100 doors, switching yielded a winning door 100% of the time.

When this entire argument first surfaced in Marilyn Vos Savant’s article in PARADE magazine, the world was against her. She was clearly swarmed with hate mail from many readers as well as mathematicians in the field with Ph.Ds. Using reasoning and experimentation, she was able to show everyone else the error of their ways and proved her argument valid. Vos Savant showed how learning the Monty Hall problem is similar to learning how to ride a bike. Once it finally clicks, It’s easily Comprehensible.

Works Cited:

The Monty Hall Problem” Wikipedia. 21 Mach 2014. Web. March 2014.

Game Show Problem” PARADE Magazine. 1990-1991. Web. March 2014.

Understanding the Monty Hall Problem” Better Explained. 24 September 2009. web. March 2014.

Vinny, you didn’t ask for feedback on your early draft. (Maybe you figured I’ve been so slow with your feedback that you wouldn’t benefit from asking.) Here’s where it’s needed most though, in a draft that still has a deadline pending. Let’s read it now together.

P1. I like the structure of your first sentence, but I have the usual recommendations for its execution.

—I’ll give you 2 words, not three. Choose the best 2: “absolutely fascinating riddle.”

—”seems to stump” or “stumps”?

—”attempt to answer it” or “answer it”?

You say “This is because,” but we can’t know whether you mean the riddle stumps people or because the riddle seems to stump people, or because it stumps them on their first try but yields the right answer on subsequent tries. Does it stump them? Or does it seem to stump them?

—”nearly no” or “little”?

Your summary of the problem doesn’t indicate that one door hides a prize, a detail that would quickly explain what it means to select the “correct” door. Otherwise, we’re not in the conversation.

—”must choose one particular door” or “chooses any door”?

—”Monty hall” or “Monty Hall”?

—”another door, not including the one chosen” or “one of the unchosen doors”?

—”weather” or “whether”?

You need to say, still in your summary, that after a door is removed from play, the contestant is offered a trade. He can keep what’s behind his original choice, or choose what’s behind the other remaining door.

Call this illustration “a public domain image available from the Wikimedia Commons.”

P2. You mean a 2/3 positive outcome is achieved, right?

P3. I dispute that this explanation is clearer as you have explained it, Vinny. You haven’t said :

—that there’s still just one car, but 99 goats

—that Monty takes 98 doors out of play

—that Monty never takes a car out of play.

The reason your odds improve from 1/100 to 99/100 is that there was such a small likelihood of the car being behind your first choice. The odds that the car is behind the door Monty doesn’t eliminate are nearly 1/1. The only other (highly unlikely) place it could be is behind your original door.

But without being clear on the rules of Monty’s actions, we can’t know any of that.

P4. The first time you name your author, call her Marilyn Vos Savant. The second and subsequent occasions, you call her Vos Savant.

True, but it doesn’t help you ride a surfboard. I’m not nearly as clear (or convinced) about certain flavors of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, even after I feel comfortable about the Monty Hall.

One more thing about the persuasiveness of the “proof.” Reluctant readers will object that you’re just creating artificial probabilities by showing the unchosen doors twice. There aren’t three possibilities, they’ll say, only two.

1. I choose car and the unchosen doors are goat goat.

2. I choose goat and the unchosen doors are car goat.

[3. I choose goat and the unchosen doors are goat car.]

They would completely reject 3 as not logically different from 2. The same objection is leveled against the Riddle I offered about the Beagle Puppies. Tell me why knowing one beagle is male changes the odds of whether the other beagle is male and I’ll be sure you understand why 2 and 3 are both valid and different possibilities.

revised